We remain fully operational. Our teams are working around the clock to ensure your deliveries continue safely.

Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

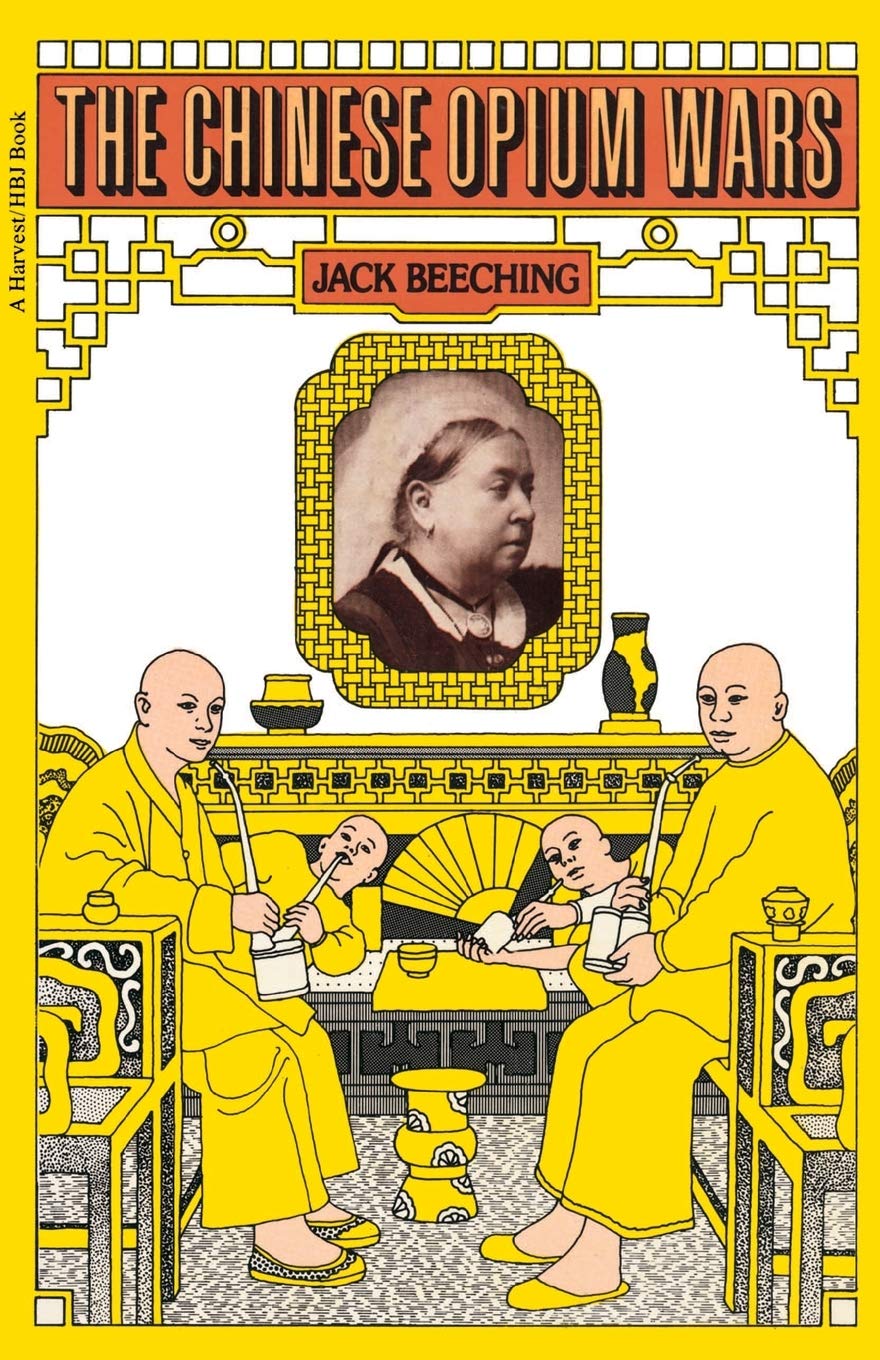

The Chinese Opium Wars [Beeching, Jack] on desertcart.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. The Chinese Opium Wars Review: Extremely Detailed - It is very well-written. I learned so much. I recommend this book to everyone. Review: British Arrogance Explicated - The opium wars in China were a contest between the Chinese and the British which extended from 1840 to 1842, and were renewed in 1857. What these wars were about is a matter of contention. Jack Beeching, in this engaging and detailed book about the conflicts takes the position that they really were about what the name implies, smuggling opium into China in violation of its laws. An analogy today, would be if Columbia or Mexico were to invade the U.S. in order to open our markets to cocaine regardless of the fact that our laws prohibit its sale. Britain had the sea power and disciplined troops to do it and did. British and American commentators at the time and since have strongly urged the view that in 1839 the real issue was not opium but extra-territoriality - or, sometimes, the Open Door in China. The argument is respectable, but it must be recognized that the British government laid down from the start a policy and a strategy which corresponded very closely to the declared needs of the big opium smugglers." Beeching is up against some fairly strong "respectable" opposition. For example, Peter Ward Fay, a professor emeritus of history at the California Institute of Technology, wrote a book about the first opium war, evidently intending to satisfy what he and Beeching must both have realized at the time they wrote, both books being published in 1975: "There does not exist, for the West's first major intrusion into China, what the subject deserves and a reader is entitled to. The popular books on the war leave it a piece in the larger story of the `awakening dragon' or treat it decidedly hurriedly. The scholarly monographs approach it from one angle or another, rarely making much of an effort at narrative." (Fay, Peter Ward, The Opium War, 1840-1842, 1975, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1997, Paperback Edition. Evidently Fay did not think much of Beeching's narrative. Writing a preface in a new edition in 1997, he said: ... "Nothing has been added to the existing Notes on Sources, in part because in the years since it was drawn up, nothing that seriously added to or challenged the narrative has to my knowledge appeared.") Fay subscribes to the other "respectable" argument. "Readers may discover that though I am quite aware what damage opium did, I do not believe that the Opium War was really about opium at all. It was about other particular things, shaped by circumstances as most history is; and it was, if you look for an overarching principle, about somehow getting the Chinese to open up. The desire is still very much with us today." This view is echoed by John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman. They argue that the British expeditionary force led by the new paddle wheel steamer, Nemesis, was intended "...to secure privileges of general commercial and diplomatic intercourse on a Western basis of equality, and not especially to aid the expansion of the opium trade. The latter was expanding rapidly of its own accord and was only one point of friction in the general antagonism between the Chinese and British schemes of international relations." (Fairbank, John King, Goldman, Merle, China a New History, 2nd Edition, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2006. It should be noted that Fairbank's review of both Fay's and Beeching's books in The New York Times is cited on the cover of each.) The objective being in dispute even today, what happened in China? The background of the conflict is complex, but the central aspect of it is generally agreed. In the eighteenth century the British had developed a substantial liking for tea. They obtained it from China for which they paid in silver. As the consumption grew the balance of payments with China tilted more and more in favor of the Chinese. For example, between 1710 and 1759 Britain bought 26,833,614 Pounds Sterling worth of tea and sold only 9,248,396 Pounds worth of goods to the Chinese. That the Chinese did not admire British goods or want them is a frequently told story. Lord Macartney took a representative selection of British goods when he went to the Summer Palace in 1793 to establish an embassy. The Emperor took one look at them and said: "I set no value on strange objects and ingenious (sic.) and have no use for your country's manufactures." They languished in a warehouse only to be discovered in their crates at the end of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. The British simply could not afford to continue buying tea and not selling anything. In India the British were growing opium (a white poppy which produces a milk from which opium is derived). While there was no market for it in 1782, the British thought they could purchase it cheaply in India where they were selling textiles and develop a market for it in China to offset their tea purchases. A couple of British firms did just that. "By 1830, the opium trade there was probably the largest commerce of its time in any single commodity, anywhere in the world." But the Chinese banned the sale and tried to shut down the sellers and importers. While the emperor had issued an edict against its sale in 1799 and closed outlets by force in 1821-3, the trade persisted. The proximate cause of the war was the righteous action of the incorruptible Chinese Imperial Commissioner, Lin Zixu, in 1839, to arrest the Chinese opium dealers in Canton and to quarantine the foreign suppliers and seize their supplies of opium. The British responded by forcibly "opening the door," but the door was to the opium den. The arrogance of the British at that time cannot be overstated. Disraeli, opposing war, challenged Palmerston, the Prime Minister to put the matter to a vote of the nation. Palmerston did just that. He dissolved Parliament and appealed to the electorate calling Commisioner Lin "an insolent barbarian." Evidently gunboat diplomacy was more popular with the people than the House of Commons, for his government was returned with a majority. It should be noted, that during this time opium was not prohibited in Britain and many there regarded it as less harmful than alcohol and, indeed, used it for medical purposes. Beeching describes the ensuing war in detail, recognizing that it was not an even contest. The British had disciplined troops and modern weapons. In one instance, after the British had captured Ningpo, the Chinese massed a force and invaded the city. They broke through a city gate and attacked down the street toward the market. The British brought up one howitzer, and a platoon of infantry which barred the only side street of escape. It was a slaughter. "No British were killed that night, but over 500 Chinese dead were counted. All units of the Chinese army which had been in action at Ningpo were permanently demoralized from the effect on their minds of grapeshot and musketry at close quarters. Henceforth, against any European army, they were defeated in advance." The treaty of Nanking ended the war and granted the British the right to resume trade on an expanded basis and other concessions. The personalities involved on both sides seem to be caricatures of their time. The British Victorian statesmen and soldiers were conquerors and the Chinese mandarins were still the foundation of Chinese society. Both empires had cracks, and Beeching describes them. However, the Chinese, being isolated compared to the British, did not recognize their weeknesses. A new emperor in 1850, Hsien Feng, was not a match for the time. There were disasters, the Yellow River altered its course and the Taiping rebellion swept the country. Parts of the treaty of Nanking were not honored. The British wanted what the treaty provided and more. They concentrated their fleet on Chinese waters after the Crimean War was over. An excuse came when the Arrow, a British flag vessel, was boarded by Chinese marines who arrested the Chinese crew. The following clash, in 1859, was even more one sided than the previous one. After another treaty was negotiated but not honored by the Chinese, the British captured Beijing. They looted and destroyed the Summer Palace and opened up the interior of China to trade and missionary activity. The Chinese Opium Wars has remained in print for the last thirty years because it is readable and its scope is extensive, from 1798 to 1864. Furthermore, Beeching dwells upon the personalities and turmoil in China along with British aggression. It may well be that the isolation the Chinese imposed upon themselves from the time of Zheng He would have dissipated over time without foreign intervention. However, Chinese social and governmental structure, which did not lend itself to change, was anachronistic. Gentry were selected to command troops without having received training other than in Confucian texts. Official promotions from ninth grade, and later eighth grade, were offered for cash starting in 1838. And the revolutions in China did not include the industrial one. Beeching describes his modest intent in a postscript referring to his sources: "Materials for the serious academic history of the Chinese Opium wars which has not yet been written are abundant. For instance there are over 2000 books and articles, many in Chinese or Russian, on the Taiping Rising alone. To append a scholarly apparatus of references to an essay in popular narrative history, compiled from less than a hundred sources, all secondary, and in only two languages, would be willfully misleading. Yet the narrative historian writing for the man in the street has valid standards of his own - corresponding to those of the responsible journalist. History is the resurrection of the dead; this book is only a sketch of a possible beginning." Given that objective, Beeching successfully outlined the conflicts.

| ASIN | 0156170949 |

| Best Sellers Rank | #830,480 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #1,033 in Chinese History (Books) #1,152 in History of Civilization & Culture #1,301 in Naval Military History |

| Customer Reviews | 4.7 4.7 out of 5 stars (27) |

| Dimensions | 8.6 x 5.54 x 0.91 inches |

| Edition | Illustrated |

| ISBN-10 | 9780156170949 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0156170949 |

| Item Weight | 15.2 ounces |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 352 pages |

| Publication date | April 6, 1977 |

| Publisher | Mariner Books |

R**L

Extremely Detailed

It is very well-written. I learned so much. I recommend this book to everyone.

R**R

British Arrogance Explicated

The opium wars in China were a contest between the Chinese and the British which extended from 1840 to 1842, and were renewed in 1857. What these wars were about is a matter of contention. Jack Beeching, in this engaging and detailed book about the conflicts takes the position that they really were about what the name implies, smuggling opium into China in violation of its laws. An analogy today, would be if Columbia or Mexico were to invade the U.S. in order to open our markets to cocaine regardless of the fact that our laws prohibit its sale. Britain had the sea power and disciplined troops to do it and did. British and American commentators at the time and since have strongly urged the view that in 1839 the real issue was not opium but extra-territoriality - or, sometimes, the Open Door in China. The argument is respectable, but it must be recognized that the British government laid down from the start a policy and a strategy which corresponded very closely to the declared needs of the big opium smugglers." Beeching is up against some fairly strong "respectable" opposition. For example, Peter Ward Fay, a professor emeritus of history at the California Institute of Technology, wrote a book about the first opium war, evidently intending to satisfy what he and Beeching must both have realized at the time they wrote, both books being published in 1975: "There does not exist, for the West's first major intrusion into China, what the subject deserves and a reader is entitled to. The popular books on the war leave it a piece in the larger story of the `awakening dragon' or treat it decidedly hurriedly. The scholarly monographs approach it from one angle or another, rarely making much of an effort at narrative." (Fay, Peter Ward, The Opium War, 1840-1842, 1975, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1997, Paperback Edition. Evidently Fay did not think much of Beeching's narrative. Writing a preface in a new edition in 1997, he said: ... "Nothing has been added to the existing Notes on Sources, in part because in the years since it was drawn up, nothing that seriously added to or challenged the narrative has to my knowledge appeared.") Fay subscribes to the other "respectable" argument. "Readers may discover that though I am quite aware what damage opium did, I do not believe that the Opium War was really about opium at all. It was about other particular things, shaped by circumstances as most history is; and it was, if you look for an overarching principle, about somehow getting the Chinese to open up. The desire is still very much with us today." This view is echoed by John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman. They argue that the British expeditionary force led by the new paddle wheel steamer, Nemesis, was intended "...to secure privileges of general commercial and diplomatic intercourse on a Western basis of equality, and not especially to aid the expansion of the opium trade. The latter was expanding rapidly of its own accord and was only one point of friction in the general antagonism between the Chinese and British schemes of international relations." (Fairbank, John King, Goldman, Merle, China a New History, 2nd Edition, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2006. It should be noted that Fairbank's review of both Fay's and Beeching's books in The New York Times is cited on the cover of each.) The objective being in dispute even today, what happened in China? The background of the conflict is complex, but the central aspect of it is generally agreed. In the eighteenth century the British had developed a substantial liking for tea. They obtained it from China for which they paid in silver. As the consumption grew the balance of payments with China tilted more and more in favor of the Chinese. For example, between 1710 and 1759 Britain bought 26,833,614 Pounds Sterling worth of tea and sold only 9,248,396 Pounds worth of goods to the Chinese. That the Chinese did not admire British goods or want them is a frequently told story. Lord Macartney took a representative selection of British goods when he went to the Summer Palace in 1793 to establish an embassy. The Emperor took one look at them and said: "I set no value on strange objects and ingenious (sic.) and have no use for your country's manufactures." They languished in a warehouse only to be discovered in their crates at the end of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. The British simply could not afford to continue buying tea and not selling anything. In India the British were growing opium (a white poppy which produces a milk from which opium is derived). While there was no market for it in 1782, the British thought they could purchase it cheaply in India where they were selling textiles and develop a market for it in China to offset their tea purchases. A couple of British firms did just that. "By 1830, the opium trade there was probably the largest commerce of its time in any single commodity, anywhere in the world." But the Chinese banned the sale and tried to shut down the sellers and importers. While the emperor had issued an edict against its sale in 1799 and closed outlets by force in 1821-3, the trade persisted. The proximate cause of the war was the righteous action of the incorruptible Chinese Imperial Commissioner, Lin Zixu, in 1839, to arrest the Chinese opium dealers in Canton and to quarantine the foreign suppliers and seize their supplies of opium. The British responded by forcibly "opening the door," but the door was to the opium den. The arrogance of the British at that time cannot be overstated. Disraeli, opposing war, challenged Palmerston, the Prime Minister to put the matter to a vote of the nation. Palmerston did just that. He dissolved Parliament and appealed to the electorate calling Commisioner Lin "an insolent barbarian." Evidently gunboat diplomacy was more popular with the people than the House of Commons, for his government was returned with a majority. It should be noted, that during this time opium was not prohibited in Britain and many there regarded it as less harmful than alcohol and, indeed, used it for medical purposes. Beeching describes the ensuing war in detail, recognizing that it was not an even contest. The British had disciplined troops and modern weapons. In one instance, after the British had captured Ningpo, the Chinese massed a force and invaded the city. They broke through a city gate and attacked down the street toward the market. The British brought up one howitzer, and a platoon of infantry which barred the only side street of escape. It was a slaughter. "No British were killed that night, but over 500 Chinese dead were counted. All units of the Chinese army which had been in action at Ningpo were permanently demoralized from the effect on their minds of grapeshot and musketry at close quarters. Henceforth, against any European army, they were defeated in advance." The treaty of Nanking ended the war and granted the British the right to resume trade on an expanded basis and other concessions. The personalities involved on both sides seem to be caricatures of their time. The British Victorian statesmen and soldiers were conquerors and the Chinese mandarins were still the foundation of Chinese society. Both empires had cracks, and Beeching describes them. However, the Chinese, being isolated compared to the British, did not recognize their weeknesses. A new emperor in 1850, Hsien Feng, was not a match for the time. There were disasters, the Yellow River altered its course and the Taiping rebellion swept the country. Parts of the treaty of Nanking were not honored. The British wanted what the treaty provided and more. They concentrated their fleet on Chinese waters after the Crimean War was over. An excuse came when the Arrow, a British flag vessel, was boarded by Chinese marines who arrested the Chinese crew. The following clash, in 1859, was even more one sided than the previous one. After another treaty was negotiated but not honored by the Chinese, the British captured Beijing. They looted and destroyed the Summer Palace and opened up the interior of China to trade and missionary activity. The Chinese Opium Wars has remained in print for the last thirty years because it is readable and its scope is extensive, from 1798 to 1864. Furthermore, Beeching dwells upon the personalities and turmoil in China along with British aggression. It may well be that the isolation the Chinese imposed upon themselves from the time of Zheng He would have dissipated over time without foreign intervention. However, Chinese social and governmental structure, which did not lend itself to change, was anachronistic. Gentry were selected to command troops without having received training other than in Confucian texts. Official promotions from ninth grade, and later eighth grade, were offered for cash starting in 1838. And the revolutions in China did not include the industrial one. Beeching describes his modest intent in a postscript referring to his sources: "Materials for the serious academic history of the Chinese Opium wars which has not yet been written are abundant. For instance there are over 2000 books and articles, many in Chinese or Russian, on the Taiping Rising alone. To append a scholarly apparatus of references to an essay in popular narrative history, compiled from less than a hundred sources, all secondary, and in only two languages, would be willfully misleading. Yet the narrative historian writing for the man in the street has valid standards of his own - corresponding to those of the responsible journalist. History is the resurrection of the dead; this book is only a sketch of a possible beginning." Given that objective, Beeching successfully outlined the conflicts.

J**E

British Empire at the peak of its power

Jack Beeching is a scholarly historian who presents the reader with unadorned facts about Britain's trade in opium and Chinese coolies (slaves) during the Victorian Age. His spell-binding tale of events in China between 1798 and 1860 depicts the British Empire as a highly commercial enterprise, employing military might, and economic theory to generate revenue. If any country, such as China and India, were economically primitive, then British tried to modernize the nation with English common law, courts, roads, and technology. Then, the economy in the backwards nation developed sufficiently that inhabitants might purchase pottery and cotton goods from England. British battleships were quick to shell Chinese coastal cities, and then to exact reparation payments. Troops were very casual about "sacking" conquered towns, raping women, and looting treasures. Victories in battle resulted in large indemnity payments, in silver, from China to England. A British officer could gain enormous wealth in the form of a "prize" (plunder), and retire to a life of indolence on countryside estates. The Chinese are portrayed as a very primitive civilization, dominated by the minority Manchurian conquerors. There were only 3 million Manchurians, compared with 50 million Chinese. The Viceroy of Canton (representative of the Manchurian Emperor in Guangzhou), Yeh Ming-chen, was a blood-thirsty fellow, who killed more than 100,000 "rebels" during his rule. Despite this, he was a literary genius, and wrote beautiful poetry. There were plenty of "rebels" because the Chinese population was oppressed by (foreign) Manchurian rulers. China lacked modern technology, and her soldiers fought battles with bows and arrows, versus British howitzers and battleships. All the action in the Opium Wars took place along the Chinese coastal cities, especially Guangzhou and Hong Kong, because these were cities that could easily be devastated by cannonades from British battleships. Chinese government leaders tried to restrict the opium trade to the south, Canton and Hong Kong, while the trading houses, such as Jardine Matheson, attempted to open up the interior by ventures into Shanghai, at the mouth of the Yangtze River, and also into northern coastal cities. The British had an insatiable appetite for tea, and a fondness for Chinese silk. The Chinese had no desire for British products--porcelain and cotton goods, because they manufactured their own porcelain (i.e. "China") and hand-wove their own clothes. In addition, Chinese leaders did not want any imports into China, because this would result in expenditure of silver. Consequently, Britain had a negative balance of trade with China, which could only be satisfied by sending silver from the British Treasury to the Orient. This imbalance was a pretext for exporting opium to China, but contemporary accounts discussed by Jack Beeching reveal that the destructive and addictive quantities of opium (a narcotic, like morphine and heroin) were well-known to both Europeans and Chinese. In 1604 the first Dutch ship arrived at Canton. In 1659, the Dutch East India Company began exporting opium from Bengal, India, to China and to Indonesia, for profit and for domination. By 1729, the Emperor of China issued the first edict against the sale or consumption of opium. In 1765, the British East India Company gained control of Bengal, and in 1778, began to export opium to China. (Although opium poppies grow in Turkey and Afghanistan, very little opium was transported overland to China, compared with the huge quantity that could be transported by ship from Bengal.) The first Opium War was fought between China and European powers (mainly Britain and France) in 1839, and the second in 1860. The main source of conflict was that British traders insisted on supplying opium, and the Chinese government resisted. The Chinese realzed that opium was debilitating their population, and was also emptying the Chinese economy of silver. They attempted to halt the practice by employing diplomacy with Britain, which was fruitless. Edicts banning opium were to no avail. Warfare resulted. In both Opium Wars, British howitzers and cannon and battleships were vastly more powerful than Chinese archers and armed junks, and victories were followed by treaties legalizing the sale of opium to Chinese citizens. The looting of the Summer Palace (near Peking) by British and French armies, was followed by gifts of plunder to Queen Victoria (a jade and gold sceptre, three huge enamel bowls) and an extravagant pearl necklace for the French Empress Eugenie. Evidently, these monarchs were deeply involved in the drug trafficking. During the nineteenth century, when China was the "sick man of Asia", Asian and European powers were nibbling away at her perimeter. Russians secured by treaty a large tract of Chinese territory in the northeast, including the port city of Vladivostok. Britain conquered Nepal, a Chinese territory, and the French were nosing around in Indochina. The Japanese and Russians made periodic incursions into Manchuria and coastal cities on the Yellow Sea. The Chinese government tried to restrict foreign diplomats and traders from activity in China because (1)they thought foreigners were barbarians (e.g. English were "red barbarians" --had ruddy complexions), and (2)they wanted to encourage exports and ban 100% of imports, to achieve a positive balance of trade, and (3) they believed that foreign diplomats were trying to steal silver and territory. Of course, China itself had "nibbled" on its neighbors' territory in the preceding centuries. When I read this book, I kept an atlas and dictionary within reach, because I needed help with some of the words, and with the geography. Most of the Chinese place-names (e.g. Canton became Guangzhou, Amoy became Xiamen) were listed in the atlas under their old and new names, and were easy to locate. I was unable to find a clear image of the Peh-ho River leading to Peking, even in the (very large) map in the Times Atlas. The maps in Beechings' book were pretty limited. A great book, opening up an area of darkness for me.

S**T

Great explanation of modern day problems caused from happenings in history.

I always wondered about the problems in Hong Kong, and this book explains the beginning of the problem. Well written and very informative.

B**E

Solid

Provides a thorough and admirably objective overview of the two opium wars and is chock full of interesting details. However, it does get bogged down by English politics at points, which drag on for far too long and are not particularly interesting. Also does not go into immense detail of the relevant battles, which I appreciate but may be a turn off for some.

J**E

Five Stars

Certainly makes the Brits look bad. Going to war to make the Chinese take their opium.

M**S

Enlightening

If you want to understand China and why it will dominate the world through peace, read this book. A reminder that China will not allow our imperialism.

L**A

A matter of trade balance and imperialism

When you read about the British Empire, there is not much about the Opium Wars. It is a curious event in the history of both countries, an event precipitated by the trade deficit of Britain, unable to pay for Chinese tea and with China not wanting to buy much from the Britons. Opium was the excuse to fix this issue and this resulted in two wars between the countries. Most people find this dispute a shameful part in the history of Britain ... I take it as it is -- that was the situation in those years and for sure China learned a lesson from all this. Trading was impose to the Chinese, it was a bloody war for them, looting is a word repeated frequently in this book, this is when Hong Kong was given to Britain and this was also an epoch of Chinese slaves trading to places like California and Peru. Chile, in the war with Peru in 1879, set free thousand of chinese slaves --- a point worth mentioning. So this book is atractive, you will find interesting facts and places, a book worth reading.

B**N

Absolut erstklassige Beschreibung der Ereignisse im Rahmen der Opium Kriege. Beide Seiten wurden in ihren Plänen und Absichten mit der erforderlichen Distanz und einer ganz phantastischen Portion britischen Humor, oder war es Zynismus, beschrieben. Der Autor versteht es, mit den Worten zu tanzen. Der Leser, dessen Englisch verbesserungswürdig ist, hat Mühe, mitzukommen. Aber die Anstrengung lohnt. Ein gravierender Nachteil: Es werden keine Quellen im Text benannt.

D**S

'Colonial' and empire histories often lend themselves to partisanship: either they present Britain as an arrogant and cynical force acting upon innocent and noble other races, or as a glorious and idealistic nation bringing peace and civilisation to grateful peoples. In the Opium Wars, Britain's opponent was the world's proudest and oldest civilisation, which has never been fully conquered. It is perhaps for this reason that Jack Beeching's book is able to avoid that tired - and to my mind over-simplistic - dialectic of 'for' or 'against', in which so many writers impose 21st century value judgments upon the events of a different age; equally it may simply be that Mr. Beeching is just a good judge of history. This book is informative, exciting to read - the description of the British navy's war upon the Chinese pirates knocks Hornblower into a cocked hat - and insightful into both Chinese and English mentalities of the day. It manages to knit together the many widely different factors that shaped relations between China and the West, from the Christian evangelism of the Victorians to the decadence of the Manchu empire and the burgeoning nationalism of the Chinese people. It leaves the reader with a view of an age that was groping its way around cultural confusions, that was brutally selfish as well as idealistic and brave, and it tells the story simply and elegantly.

A**N

I first borrowed this book from a relative of the author and was bowled over by the lucid account of what must be one of the darkest hours of the British Empire. It explained so much about our ambiguous relationship with modern day China to which I was making several visits. I was keen to own a copy but they were hard to come by. This volume that had previously been in a library was in remarkably good condition. Having been plasticated even the sleeve was in excellent shape. Well done cheshire_booklover. I am very happy and excited to read it again.

E**1

Book arrived in good time and all as described

Trustpilot

2 days ago

5 days ago