Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Warehouse # 7, 4th Street, Umm Ramool, Dubai, 30183, Dubai

Full description not available

G**E

Who chooses God's elect?

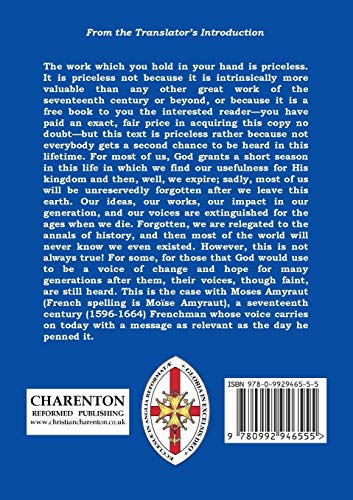

We’ve waited 383 years for this translation, so why should it be important? The issue at stake has been exercising Christians for 2000 years: it is about the loving and holy God of the Bible, sinful and rebellious fallen man, and how the two can be reconciled, commonly called man’s salvation or redemption, through the sacrifice of our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ, on the cross at Calvary. Moïse Amyraut (1596-1664) was a leader of French Protestant Christians, called Huguenots, and he was defending the doctrines of the Christian faith in the early years of the Reformation when the details of how salvation was effected were controversial and of great interest. He followed in the tradition of John Calvin, the father of the Huguenots. Doctrinal details had been spelled out very carefully in the French Confession of Faith of 1559 and the Belgic Confession of Faith of 1566. This theology, as exaggerated by Calvin’s successor Theodore Beza (1519-1605), was subsequently contested by Jacob Arminius (1560-1609) and the divergence of opinion that he expressed has crystallised over the years into Calvinism v. Arminianism. The Synod of Dort was convened in Dordrecht in Holland in 1618-19 to make a judgment upon five points that followers of Arminius had drawn up disputing the Calvinistic doctrines, especially those concerning election, as described in the Belgic Confession. The Synod rebutted the five points in the Canons of Dort. Amyraut published his brief treatise on Predestination in 1634, supporting the Canons of Dort, and providing additional clarification on the nature of predestination. He was a Professor of Theology at Saumur in France, used to writing treatises in Latin, but wanting to reach beyond academia, he wrote it in French so that it would be accessible to as many as possible.Predestination refers to God ordaining the course of events, an issue that is recurrent throughout the Bible, from the creation of the world, to the fall of man, to Noah’s flood, to the Exodus, to the coming of Jesus Christ, His crucifixion and resurrection, and to the Day of Judgment. But it seems to impinge on our freewill, because if God has ordained everything, how can we be held responsible for our actions? Salvation, the forgiveness of our sins and everlasting life all depend on our willingness to repent and believe the gospel. And the Bible speaks as if the choice is ours, that whoever believes in Jesus should not perish but have everlasting life (Jn 3:16), and that God is not willing that any should perish but that all should come to repentance (2 Pet 3:9). Yet, not all do come to repentance. Some get saved, and some don’t. On the face of it, there are seeming contradictions: if God has ordained the course of events, man doesn’t have freewill, and how is it that God is not willing that any should perish, yet some do?There are two issues at stake here. The first is freewill and the responsibility that goes with it, which, according to the Bible, separates man from the rest of creation, because God said, ‘Let us make man in our image … and let them have dominion … over all the earth.’ (Gen 1:26) So man alone has this spiritual attribute, and how he uses it must be of prime importance to God and man. The second is the integrity of the Bible, the word of God, since all Scripture is given by His inspiration (2 Tim 3:16), so a seeming contradiction needs very careful consideration, in the expectation of gaining a better understanding of God’s revelation to man.In his admirable discourse, Amyraut distinguishes between the offer of salvation and predestination to faith. The first of these is universal for all mankind but it is conditional, conditional upon each believing. This does no damage to the ‘whoever’ of Jn 3:16 or to God not being willing that any should perish. But it is conditional. While it could be argued by true believers that every right-minded man should believe in Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of his sins and for everlasting life, mankind generally is angry at his condition and hostile to God, cynical and unwilling to consider the gospel. Would it be right to bring such into heaven? Could such possibly have fellowship with God? While the offer is to all, many show themselves unworthy by their unbelief. Indeed, so serious is the fall of man, that we may ask if any of us in our fallen state would ever believe and become worthy of so great a salvation. Could it be that the Son of God should offer such a precious sacrifice of His Very Self for redeeming the whole world, provided they would only believe in Him, yet not one of us would voluntarily call upon His name? What a terrifying thought, that our Lord Jesus should pay such a price yet not save a single soul from hell. Shocking thought indeed. Yet, knowing our own depravity of heart, might this indeed be very close to reality? If it weren’t for God’s grace, would I have believed?This brings us to predestination to faith. Amyraut conjectures that none of us would have believed of our own accord, even though it would only have been reasonable to do so. So that our Lord Jesus should have children, indeed a bride, God chose some before the foundation of the world to be predestined to faith, who would truly believe, not against their will, but through the sweet working of the Holy Spirit, convicting us of sin, and righteousness and judgment, revealing Himself to us until we willingly bow the knee. Did God choose the good ones to believe in Him? No, lest anyone should boast. So salvation is all of grace, and God has chosen his elect before the foundation of the world (Eph 1:4).Dr Matthew Harding, the translator, has endeavoured to be technically accurate while coping with, what he admits in a preamble, Amyraut’s verbose style. The resulting book is not an easy read, but then it is not an easy subject. There is more in it than I have described, notably about those who in their lifetime never hear the gospel; also Amyraut explains how the knowledge that he is predestined to faith is a great comfort to the believer, strengthening him for the persecution he can expect in this hostile world. There is also an excellent biographical outline of Amyraut’s life by Dr Alan Clifford.What I have outlined is a middle way, between 5-point Calvinism and Arminianism, sometimes referred to as Amyraldianism. It can be referred to as 4-point Calvinism, because it rejects ‘limited atonement’, the assertion that Christ only died for the elect, not for the whole world. Limitless atonement would be representative of Amyraut’s view, and of Calvin’s view also, because 5-point Calvinism got honed into shape by theologians subsequent to Calvin. Dr Clifford refers to this middle way as Authentic Calvinism.As a postscript to this review, Amyraut was a peer of René Descartes, also born in France in 1596. They may both be considered philosophers. Amyraut believed in revealed truth, truth revealed to us by God through the Bible, God’s holy word, with the help of the Holy Spirit, who leads us into all truth. Descartes rejected all tradition as untrustworthy, and as a founding rationalist, only accepted as true what he personally could not possibly doubt. Both were aware that truth was something peculiar to mankind and very precious. Descartes needed a belief in the goodness of God to validate his confidence that truth even existed. Both wanted to enlighten mankind with the truth. Both, very unusually, recorded their controversial ideas in French to reach beyond academia and the establishment.Subsequent rationalists have forgotten or have chosen to ignore that Descartes needed God for the assurance that truth exists, and we have descended to an age of atheistic materialism. While Descartes is heralded as the originator of modern philosophy, with his iconic statement ‘I think therefore I am’, an assertion of human consciousness, our culture has moved on. By contrast, the gospel of Jesus Christ, what was to Amyraut the pearl of great price, remains unchanged and the hope and glory of every true believer.

Trustpilot

1 month ago

3 weeks ago